The Village Green showing the first kiosk, a concrete model known as the K3.

Telephone numbers these days are eleven digits long. But for nearly 60 years people in Hoxne could dial each other using just three. And if you were lucky enough to have a phone in the early 1930s, it would have taken only two digits to reach another Hoxne subscriber (as phone users were called in those days). In fact the very first number to appear in the phone books under the village’s name had a single digit. It was Hoxne 1. But we’ll come to that later….

Communication by electricity between Hoxne and the outside world began in the 1880s. Kelly’s directory for 1888 shows the post office was also a telegraph office. A machine had been installed to receive and transmit telegrams - one letter at a time - along a copper wire linking Hoxne and Stradbroke, via Scole, to Diss and the national telegraph network.

The telephone followed much later. Although it was invented in 1876 it took 30 years to reach the Waveney Valley. Only one person in Hoxne availed himself of it at first - the chap at the big house. Engineers put up a line of poles and wires to connect Samuel Hill-Wood’s grand home of Oakley Park to the post office in Eye. There, the new switchboard came into operation in January 1907 and Mr Hill-Wood was given the number Eye 18.

He would have had to pay a hefty rental on the four-mile line to Eye - about £40 a year, or the equivalent of £5000 today. It’s not clear why Oakley Park wasn’t connected to the telephone exchange at Scole, which was a lot closer. Perhaps it made it simpler for Samuel’s wife to ring her mother, Lady Bateman. Her home - Brome Hall - was also connected to the exchange at Eye.

When the Hill-Woods left Oakley Park in 1912, the line appears to have become disused. But at least part of the route of telegraph poles came back into use in later years; to this day, Hoxne South Green is still served by the Eye exchange.

The next telephone in the village arrived in 1923. It was installed in the post office in Low Street, as part of the postal service. Callers from further afield could ring up and dictate a message to be delivered on paper to addresses within a mile of the post office for 6d, plus the cost of the call.

Two years later, the same line was opened up for public use. The Hoxne Rural Call Office, as it was termed in the 1925 telephone directory, was probably a ‘silence cabinet’ - a wooden telephone box inside the post office (which was also the grocery and drapery store, Mutimer and Sons). A member of staff would place the call, transfer it to the box, and the caller would pay for it afterwards at the counter.

A silence cabinet typically used for rural call offices (Picture: BT Archives).

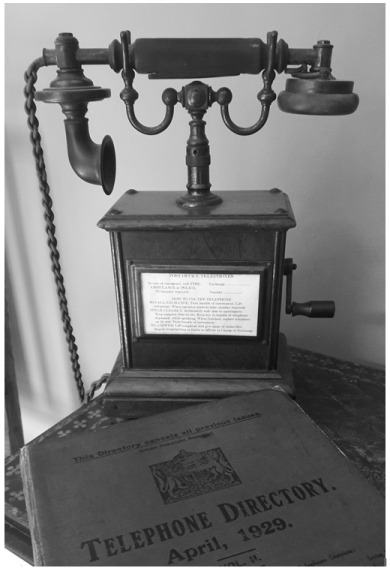

The number of the call office was Hoxne 1. In reality it was connected to the exchange at Diss. Hoxne still didn’t have its own exchange so anyone in the village wanting their own telephone had to pay a ‘long line’ charge to get a connection to Scole exchange. In 1926 the village doctor Herbert Christal had a phone installed at The Firs - Scole 10 - and the following year the auctioneers Moore Garrard and Son at Elm House became Scole 12. (The Scole exchange worked on the magneto system which was already obsolete by that date. Subscribers had to turn a generator crank to call the operator, ask for the number they wanted, then turn the handle again when the call was over.)

A magneto telephone of the kind possibly used at The Firs and Elm House, Hoxne, between 1926 and 1931.

(Picture: BT Archives).

For the village to get an affordable telephone service, it needed its own exchange. In the 1920s, the GPO demanded a minimum of eight people to sign up before it would consider installing one. Normally, as at Eye and Scole, this took the form of a manual switchboard in the post office where a member of staff would act as operator and connect the calls - provided they weren’t busy serving customers in the shop. And at such places, there was no telephone service at night or on Sunday afternoons.

Luckily for Hoxne, by the time enough would-be subscribers came forward, technology had moved on. The RAX - or Rural Automatic Exchange - had been developed, providing a 24-hour service without the need for human operators. And Hoxne was chosen to get one.

A small brick building was put up on the road to Syleham to house the switching equipment. Telephones with dials were installed in the homes and businesses it was to serve. Each was given a two-digit number - the call office became Hoxne 21, the doctor’s number changed from Scole 10 to Hoxne 25. Among the new subscribers was Kingsbury’s bakers in Low Street on Hoxne 28 and the police house (Hoxne 29).

Hoxne telephone exchange, built in 1931, with the later extension behind.

The exchange came into use on 17 August 1931. Hoxne subscribers could dial one another directly, but they still had to ring the operator in Diss - by dialling 01 - for calls to anywhere else. The following year, the exchange’s coverage area was extended to Brockdish and Thorpe Abbotts.

The equipment ran on batteries and a small generator kicked in to recharge them when they ran low. So phone conversations in Hoxne were petrol-powered until the arrival of mains electricity in the area..

To take advantage of this round-the-clock service, a new roadside kiosk was put up on the village green. The familiar cast-iron K6 box hadn’t been designed by then, so the first kiosk was a concrete model known as the K3, painted cream and red. Inside was a black bakelite telephone and a coin-collecting box. A local call cost two old pennies.

But there was a down side to these changes. The growing number of phones were all connected by overhead wires. The small poles which had carried the early telegraph wire to the village and beyond had morphed into giant versions, carrying broad cross arms and dozens of insulators. A line of them marched down the middle of Low Street. In Suffolk: A Shell Guide, published in 1960, its author Norman Scarfe wrote of Hoxne being despoiled by ‘outrageous wires and poles’.

Low Street with one of the Telegraph Poles mentioned above.

One particularly tall pole at the top of Church Hill carried an enamel sign (still in place in the 1970s) warning that ‘Persons throwing stones at the telegraphs will be prosecuted’. Aesthetes weren’t attacking them; small boys used the china insulators for target practice. The overhead wires were vulnerable in other ways: in December 1934, a double decker bus crashed into a pole on the A143 in Scole, smashing it in half. Hoxne exchange was cut off until the pole could be replaced.

The era of Hoxne’s two-digit phone numbers was surprisingly short. By 1937 Fressingfield and Stradbroke had been equipped with the next generation of exchange, the three-digit UAX 12, so Hoxne was upgraded too. Most existing phone numbers were prefixed with an extra ‘2’, and it became possible for Hoxne folk to dial directly to the other two exchanges.

In the bitter winter of 1947, the snow and ferocious gales took their toll on the overhead wires and many phones in Hoxne were put out of action. But it was another telephone-related problem which made it to the pages of the Diss Express that February:

‘A new kind of thief has made his or her appearance on the scene at Hoxne—a person who removes the directories from the telephone kiosk on the green, opposite the Post Office In Low Street and “fails” to return them. Three times within the last few months this has happened. After the second disappearance the village sub-postmaster (Mr. H. T. Goldsmith) on obtaining a fresh supply tied them to a shelf in the kiosk. Undeterred, the visitor or visitors untied the string and once more those users of the telephone who went to check on the number they wish to contact have to bother the Post Office or Exchange.’Throughout the 40s and 50s, the number of subscribers grew steadily. The exchange building was eventually expanded to accommodate extra switching equipment. In 1958, Hoxne’s ‘parent’ exchange in Diss was automated. Hoxne now had access to the speaking clock, the 999 service and direct-dial access to more exchanges. ‘Local’ calls - within a 15 miles radius - cost a few pennies and were untimed. For longer-distance (or ‘trunk’) calls you still had to dial 0 and ask the operator to connect you. These were much more expensive: a call to Norwich, for example, cost one shilling (equivalent to £1.25 today) for just three minutes. However, the system was open to a primitive form of hacking. Some distant exchanges could be reached - highly illegally - by stringing local dialling codes together. It was widely known in Hoxne that you could get through to Norwich for the price of a local call by dialling 994379 - if you dared.

In the 60s the more unsightly telegraph poles were removed and many of the wires were buried. The Low Street kiosk - now a K6 - was moved away from the roadside and placed to the left of the old post office. In 1971, Subscriber Trunk Dialling arrived. Hoxne subscribers could make their own calls to all the major centres in the UK without going through the operator. And in 1981 International Direct Dialling came to the exchange.

The mechanical exchange equipment with its clicking relays and whirring electro-magnetic switches continued to function through all this and eventually served about 800 customers (as they came to be called). It was finally switched off in July 1994 and replaced with an electronic switching system. Everyone was given a six-digit number beginning with 668.

Any sadness at losing the old system must have been outweighed by what was gained, such as touch-tone dialling, caller ID, 1471 and crystal-clear sound (the old exchange could be decidedly crackly). And, eventually, the rollout of broadband.

Within a few years telephone landlines as we know them will no longer exist. Exchange names have effectively disappeared already. And once fibre replaces the network of copper wires, the exchange building which has served the village for more than 80 years will be surplus to requirements.

There won’t be a telephone exchange in Hoxne any more. But, strictly speaking, there never has been. The Hoxne exchange is actually in the parish of Syleham.

Article researched and written by

John Cranston.

John is the son of Raymond Cranston, landlord of the Swan 1970/71.